The first couple miles up Mt. Whitney were downright pleasant. The trail wound up a canyon, passing by pretty alpine lakes along the way. But then the snow got thicker and thicker. By the time we had gone 4 miles, we were above the tree line and couldn’t see the trail. The landscape was all snow, ice and rock. More snow was coming down and we couldn’t see the sides of the mountain. We got to where we thought Guitar Lake (which is shaped like a guitar) was, but we weren’t sure – it was frozen and we couldn’t make out the edges of the lake. We hiked up a nearby slope and figured out that we’d been right – that was indeed Guitar Lake, and we were now way above it – about a quarter mile from the trail. It was getting late and we decided to just camp right there. There wasn’t anywhere good to camp, so we did the best we could on the bumpy, icy rocks.

As the day faded, it got much colder and windier. We didn’t have much shelter from the wind. My tent wasn’t made for these kinds of conditions, but it had to do. Nathan (who had the same kind of tent) and Frank decided to share Frank’s tent. After doing the best we could to cook hot meals, we settled down to a miserable night. We were at about 12,000 feet and the high cliffs of Mt. Whitney funneled all the bad weather right on top of us. I had to invent new ways to tie my tent down, and even then I thought it might rip apart at any minute. My warm moist breath condensed and froze on the inside wall of my tent, then the wind knocked the little ice crystals back on me, where they melted. It was snowing inside my tent. I put on all my clothes, snuggled in my sleeping bag and hoped for the best. I was able to get a few decent hours of sleep. At one point in the middle of the night, I peeked my head out of the tent. I was presented with a landscape from another planet – it certainly didn’t look like earth. There was a break in the clouds and all the stars were out. With all the snow, it was bright enough to see everything. We were surrounded on 3 sides by massive dark vertical cliffs rising some 2000 feet to the top of Mt. Whitney. It didn’t look like anything could survive long in such a place. Before going to sleep, we had all agreed that if the weather didn’t break overnight, we’d give up on Mt. Whitney.

Morning came, and the clouds returned. We couldn’t see the top of the mountain, so we decided to head back down. We had looked forward to climbing Mt. Whitney, so it wasn’t an easy decision… but it was the right one. On the way down, we passed some other members of our loose group. They were headed up Mt. Whitney. I wasn’t sure how they’d fare, but we told them what we knew of the route through the snow and wished them luck. Nathan, Frank and I made it down to the ranger station by late morning. We had some hot food and decided that we’d try to make it over Forester Pass that day. It was about 20 miles away. Both Frank and Nathan had family members coming out to meet them on the trail for re-supply. They were supposed to be at the Kearsarge Pass trail junction by noon the next day. That was about 18 miles past Forester Pass, so they had to keep moving (I’m not sure why they thought they’d have time to climb Mt. Whitney).

So, we headed out. The snow had caught up to us again, and it continued snowing on and off for much of the day. It was never a really heavy blinding snow, it was more of a light wet snow. It was actually very pretty. We were hiking on steep mountainsides underneath huge trees highlighted by the snow. Along the way, we had some excellent views of the mountains to the south and west. About halfway to Forester Pass, we passed Helen coming the other way. She was hiking the PCT with her dog. I had heard about her, but this was this first time I’d met her. We talked briefly while the snow came down on us. She was headed back to Cottonwood Pass & out to town. She had gotten close to Forester Pass, but didn’t feel confident that she could cross safely with her dog. She was supposed to meet her husband at the Kearsarge pass trail junction (the same place we were headed). We agreed to give her husband the message that she was taking another route.

We hiked a little further and passed Spice and Kurt who were camped near a stream. John had been hiking with them, but he only got as far as the base of Mt. Whitney and then turned around. He was hiking out to town over either Cottonwood or New Army Pass. We continued on. Just before the final few miles to Forester Pass, we passed another hiker who was just out for a week. We told him where we were headed. “Oh, Forester Pass… you can’t miss it. Just a couple more miles up this valley.” He sounded reassuring, we didn’t think we’d have too much difficulty with Forester Pass. Forester Pass is the highest point of the Pacific Crest trail. It’s at 13,200 feet, and located on the mountain ridge which separates Sequoia National Park and King’s Canyon National Park.

We soon passed above the last of the trees at about 11,000 feet. The trail was mostly covered with snow, but the weather had started clearing up and we could figure out where to go by looking at landmarks. The trail wound around two large alpine lakes. Then there were switchbacks up opposite side of the valley and over the ridge at Forester Pass. When we were still a few miles from the pass, we had a good view of the entire valley. We saw a prominent snow wall at the end of the valley and figured it was Forester Pass. The switchbacks appeared to be covered by snow. We walked all the way to the base of the snow wall and started zigzagging up it. It took a lot of effort, and we were glad we had our ice-axes with us. If we slipped, the ice-axes were the only thing that would prevent us sliding all the way to the bottom (if you fall, you need to drive your ice axe into the side of the cliff like a brake – a technique called a self-arrest… although it can be a little more complicated than that). Nathan was in front, I was in the middle, and Frank was last. When I saw Nathan reach the top, I expected him to jump up and down and shout!, but he just sat there. I soon realized why. I reached the top and looked down the other side. It was a cliff straight down. This wasn’t the right pass. Frank caught up to us and we told him the bad news. We looked at the map and realized that Forester Pass was actually a small nook in the mountain ridge about a quarter mile to our west. The switchbacks went through a boulder field and weren’t readily visible. I could have kicked myself for being so stupid. It was totally obvious by just looking carefully at the map.

We had a choice to make: we could either slide back down the snow wall and start at the bottom again, or we could traverse across the boulder field and pick up the trail halfway up the mountain. We finally decided to try going across the boulder field. It didn’t look too steep or difficult from where we were standing. On top of that, we were kind of impatient and realized that it would take a long time to go down and then all the way back up the trail. It was already getting a little late, so we got moving right away. We hiked across in the same order as earlier.

After about 15 minutes of climbing across steep snowy boulders, it became apparent that we were getting in over our heads. Nathan had shot ahead, out of sight around the ridge. Frank was doing his best to keep up behind me. The mountainside was getting steeper all the time, and the trail was still nowhere to be found. As we were slowly making progress around the mountain, Frank looked below and noticed the small figure of a person 1000 feet below us. We quickly realized that it was Nathan. “what happened?” we shouted. “I fell” came the reply. We continued our long distance shouting conversation. Nathan wasn’t hurt. I looked ahead and saw exactly where he had fallen. His footprints went halfway across a steep granite wall and then disappeared. I’m not sure what he was thinking, there was no way I was going to try crossing there. We happened to be standing on what was probably the only flat spot on the entire mountainside. It was a rough area about 3 feet by 7 feet protected from the edge of the cliff by a large flat boulder. It was getting late, and we decided that the smart thing to do was to camp right there. So, Frank and I did our best. We put on all our clothes, covered ourselves with whatever tarps we had, and tried to make a hot meal. It was an extremely uncomfortable night – the second one in a row. The ground was far from flat. I only had one position in which to try and sleep, and that cut off circulation to my arm. I slept for 20 minutes at a time, maybe getting 4 hours of total sleep all night. Frank said he didn’t sleep at all. We were on a cliffside at about 13,000 feet. The wind blew snow on us all night, and we had nowhere to go. I spent most of the night trying to weigh my options. It seemed that I could either go back the way we came, or try to do a controlled slide down the mountain, near where Nathan fell.

Morning finally came. Frank had decided during the night that he couldn’t get off the mountain by himself. He had a hard time just getting to the point we were at, and didn’t want to take any more risks. I tried convincing him that he could do it, but I quickly realized that his mind was made up. I didn’t want him to try something he wasn’t mentally prepared to do, so I just agreed with him. If I found an easy route though, I would try and talk him through it. The first thing I tried to do was head back the way we came. The problem was that all the melting snow had frozen overnight, and now everything was covered in a sheet of ice. I gave up on that idea, and tried heading down next to where Nathan had fallen. I went about 15 feet and got stuck. I couldn’t take another step without falling, and I couldn’t get back to Frank due to the ice. So, I just stood there. I figured that the sun would eventually hit me and start melting the ice. While I was stuck, we continued our conversation with Nathan (who had camped on the snow 1000 feet below us). We told him that Frank wasn’t going anywhere and that he should go back and get “help”. From where, I had no idea. So, Nathan put together his stuff and headed back down the trail toward where we came. I just stood there, watching his figure get smaller and smaller until it finally disappeared. I was getting a little tired. I was standing on one leg, with one hand on the mountain and the other holding my ice-axe, planted underneath me. The view was first-rate, the mountains surrounded me. Every rock and ridge was highlighted by a thin layer of fresh snow. There were two huge frozen lakes below me which would periodically crack, sending a sharp thud up the mountainside. Everything was rock and snow. About an hour later, I saw a couple dots on the horizon headed our way. Frank and I speculated who the dots might be. A few more dots appeared, and in time these people had worked their way back to us. Nathan had returned with some of the other people we knew – the same ones we passed on Mt. Whitney (they turned around before getting to the top of Whitney). When they got close enough, they shouted that there were no backcountry rangers – it was too early in the season, the fastest way to get help was to head north over Forester Pass, then east over Kearsarge Pass to town. By this time, it was sunny and getting warmer. The weather had cleared up a lot, and there were puffy white clouds in the sky. The ice around me started to melt, and I decided to head down. I first went back up to Frank and gave him some of my things – some extra food, my sleeping pad, my stove, etc. Frank could use most of this stuff, and my load would be lighter without it. I headed down the boulders. It was pretty slow going, but I finally made it to a section of the trail below me. I hugged the first person I saw. I realized that it was probably best for Frank to just stay there. I didn’t have an easy time getting down, and Frank probably wasn’t in the right state of mind to try. So, reunited with the larger group, I headed up over Forester Pass leaving Frank on the side of the mountain. We left a note on the trail below Frank to let other hikers know he was there. We hoped at least some of us would be able to get a phone by that night.

It turns out that Nathan actually had fallen twice. He first fell about 20 feet from the area where I saw his footprints end. Miraculously, he didn’t land on his head or break a bone. He then kept traversing and soon fell another 15 feet. By that time, he finally figured the safest course was slide to the bottom of the mountain.

It took a while, but we finally made it over Forester Pass. It was a lot easier going up the trail route than going up the snow wall, but it still required a good deal of caution. At the top, we were greeted by a sea of endless white peaks stretching from our feet to the ends of the horizon. I had seen a lot of amazing scenery already, but this just blew me away. I felt tiny and insignificant while looking at the vast beauty laid out in front of me. More than anything, I just felt lucky to be there.

The trail was still buried under the snow. We tried to follow its path though, and we occasionally came across small segments which were clear. We worked our way down to the tree line in the valley below and headed downstream of the now roaring Bubb’s creek. It was a long haul. I was pretty worn out from the last couple of days, and the soft snow didn’t help things. Every few steps the snow would give way and we’d sink up to our knees. Postholing through the snow is no fun. We finally found the bare trail again and kept going. By the time we made it to the Kearsarge Pass junction, it was 4pm. It was still another 9 miles up over 11,760 foot Kearsarge Pass and down to the trailhead road.

There were two people waiting at the junction. Helen’s husband Larry, and a solo hiker named Fearless. We gave Larry the message from Helen. There was no sign of Frank’s or Nathan’s families (who were supposed to be there at noon that day). Nathan and I were too wiped-out to go on, so we camped with Fearless at a nearby lake. Everyone else headed out over Kearsarge Pass.

I finally got a decent night’s sleep. Although I was still worried about Frank, I figured that everything would work itself out… it always did.

We woke up to another frosty morning. Nathan and I started heading toward Kearsarge Pass around 9am. After about an hour we came across much of Nathan’s family. All 3 of his sisters were there, headed down the trail to meet him. They had been going through their own ordeal. They told us that Kearsarge Pass was really snowy… it took them longer than they had planned. Additionally, one of Nathan’s sisters had injured her ankle and couldn’t walk very easily. Frank’s daughters had been hiking with them and they had all met the rest of our party the night before. After hearing about their dad, Frank’s daughters decided to head back to the trailhead.

We split-up the load that Nathan’s injured sister was carrying, and headed back up Kearsarge Pass. We had continuous mountain vistas all the way up to the pass and down Onion Valley on the other side.

Although the mountains were beautiful beyond description, they were also an element to be respected. I had entered the Sierras only thinking about all the good things that awaited me. I learned that these mountains weren’t there just to be admired, they were also there to teach valuable life lessons. The consequences of failing these lessons were dire indeed.

On the way down, I caught up to Frank’s daughters. I told them that their Dad would be OK. He wasn’t in immediate danger, he just felt it would be safest to stay put. They had already come to that conclusion, but were still worried about him. I got to the trailhead before they did, and I couldn’t believe what I saw – there was Frank, with a big smile and outstretched arms. A mountain rescue crew had come for him at 8am that morning. A couple climbers helped him down the mountain and choppered him back to town. He’d gotten a ride the 20 miles or so to the trailhead. He told me that later the previous day, all the snow on the side of the mountain melted. He could have walked down with a little care. But, since we’d already gone for help, he stayed put.

A short while later, Frank’s daughters arrived at the trailhead. Needless to say, they were overjoyed to see their dad. After the emotional reunion, we all got in their car and drove to town.

We arrived at a motel in Independence, CA and there was a note from the other hikers which said they went to Lone Pine, CA… a few miles down the road. We finally made it to Lone Pine in the middle of the day. The hikers who had called help for Frank hadn’t reached a phone until 11pm the previous night. It turns out that there were three incidents in the mountains that day; Frank on Forester Pass, a climber who got stuck on Mt. Whitney, and an unidentified body. Everyone was lounging around outside the motel, talking and trying to unwind. A few of the hikers were worried about John, he hadn’t been seen in town and should have been there by now. I wasn’t too concerned though, he’d disappeared before and always showed up with a big smile and a funny story. About an hour after I arrived in town, the sheriff pulled up to the motel. He informed us that they had identified the body. Sadly, it was our friend John.

I just couldn’t believe it. There had to be some kind of mistake. Everyone there was stunned, then quickly overcome by a wave of emotions. This kind of thing wasn’t supposed to happen. We weren’t taking death defying risks, we were just hiking a scenic trail. I could see how someone might get injured and have to quit hiking… but killed? It just didn’t seem right. Until then, the trip had been one long happy joyride. That mood changed instantly. I spent the rest of the day milling about, trying to do something which would take my mind off of the sad truth. But in everything I did and everywhere I went, thoughts of John were with me. I didn’t know John really well, but everything I knew about him was good. I thought about all the times I met John on the trail…

The first time I met John, I was in Idyllwild eating breakfast. He was at the table across from me. It had snowed the previous night and he had slept outside in his tent. He said that it was actually quite nice that night, not too cold at all. The rest of us had stayed in the motel.

The next time I met John was in the mission creek river basin north of San Gorgonio Pass. His poncho had fallen off his backpack and he was wondering if we had seen it. I had seen it, but I neglected to pick it up. If I had known it was his, I certainly would have. He didn’t seem too upset that it was missing, he said that it was too heavy anyway.

I ran into John next on the slopes of Mt. Baden-Powell. He was headed down the mountain and Nathan and I were headed up. He said that he got near the top and lost the trail. He was uncomfortable hiking in the steep snow and planned on skipping ahead by hiking a section of the nearby road. Nathan and I followed John’s footprints almost all the way up the mountain. He had nearly reached the top… just a couple hundred more yards.

Nathan and I passed John a day later. He was camped next to a small stream. It was 5pm and he’d called it a day. He certainly knew how to enjoy being out there. Nathan and I trudged along until about 8pm that night and collapsed in our tents. I had to wonder who was hiking with the better strategy.

John was in Agua Dulce during the same time that I was there. He enjoyed the hospitality of Donna and Jeff along with the rest of us. He left a day before I did.

I caught up with John again a couple days later. It was extremely hot in the hills north of Agua Dulce. I remember passing John while he was taking a quick break in the shade. I joked to him that it was breezier in the next shady patch, 20 feet up the trail. He stopped there too.

John caught up to us at the home of Jack Fair and camped outside. He left really early the next morning to avoid the searing midday heat of the Mojave. We camped that night at the same location, next to a river in the hills north of the Mojave.

John stayed at the same crummy motel in Tehachapi where the rest of us stayed.

The next time I met John was just after our ordeal with Amigo. Rick had given us a ride to a trailside campground, and weren’t expecting to see anyone we knew. But there was John with his friend Kurt, relaxing at a picnic bench in the campground. It turns out that John had an ordeal of his own, he missed a turn in the trail immediately outside of Tehachapi. He couldn’t find the trail, got frustrated, and decided to just skip ahead to the next stop. Kurt was worried about him in that section (he kept leaving notes on the trail for John). Nobody knew where he was. It turns out that he was in a hotel, resting and relaxing for 3 days. He and Kurt had just reunited and were in particularly good spirits.

The next morning, John helped us slack-pack to Kennedy Meadows. He got a ride there and had agreed to watch & handle all our heavy stuff until we arrived. When we got to the store there was John, drinking a beer, smiling and joking. All our stuff was laying against a nearby wall. John shared the campground at Kennedy Meadows with the rest of us. He left a day before me with his friend Kurt and Spice. The last time I spoke with John was near Cottonwood Pass. Although the weather had been getting nasty, he was wearing shorts and in good spirits. The last time I saw him, he was headed to camp near a little tarn just before Sequoia National Park.

John hiked as far as the base of Mt. Whitney before deciding to turn around. He had two passes to choose from. He could take nearby New Army Pass, which was closer and quicker, but less traveled. Or, he could go all the way back to Cottonwood Pass. He chose to hike out on New Army Pass. At some point, he took a wrong turn. He walked over a steep icy patch and fell about 50 feet. He was 69 years old.

We spent the next day in Lone Pine trying to make sense of what had happened. John’s family came up from San Diego that night. We decided to get together in a nearby park the next day and have a remembrance service for John. I’d been to these kinds of things before, but this was different. Instead of a dark, sad, impersonal ritual, we had a sunny day in the park. It was a celebration of the life of a wonderful man. Everyone said a few words about John. We were all very sad and grief-sticken, but being among friends and John’s family made it easier. A lot of the hikers dedicated the rest of their hike to John. I embroidered his initials on my backpack. I figured that at least a part of him would get to travel the rest of the PCT. By the end of the day, I realized that the essence of John’s spirit was still alive in everyone he touched.

The best way to get past the shock of John’s death was to get back out there. None of us had been able to climb Mt. Whitney due to the weather. It was now nice and sunny, so we decided to give it a shot from the other side of the mountain. There’s another trail which goes up Mt. Whitney from the east. We got a ride up to the Mt. Whitney trailhead, hiked about 5 miles up the mountain and camped.

I started hiking at about 9am the next morning. Most of the other hikers were already well on their way. The trail up Mt. Whitney was long and winding… much like the PCT. We went up countless snow covered switchbacks, and finally arrived at Whitney Portal – a point along the mountain ridge where the trail from the PCT joined the one we were on.

We had views back down to the Guitar Lake area, where we had been a week earlier. It looked a lot different already. Much of the snow had melted, and the edge of the lake was plainly visible. The final walk along the ridge to the top of Mt. Whitney wasn’t terribly difficult, but it was long and tedious. I was only hiking with one other person at this point, Donna. The rest of our “group” were already on their way down. We finally reached the top around 4pm. Mt. Whitney is a really popular hike during the middle of the summer. It’s difficult to get a permit to hike to the top, and still the trail can be awash with people. We were here in the beginning of June, so it was a lot less crowded. There were a few people up there, but not too many. There’s a stone shelter on top of Mt. Whitney and a couple of plaques (just in case you didn’t know where you were). At 14,496 feet, Mt. Whitney is the highest point in the lower 48 United States. There are a number of mountains almost as high, but Mt. Whitney has top honors. Of course, the view from the top was great. To the east, we could see the town of Lone Pine in the desert valley below. To the south, Olancha Peak rose above rolling green mountains. To the west, the mountains tapered off in the distance, eventually giving way to the central California valley (which we could not see). To the north, the white-capped mountain peaks went on and on and on. That’s where we were headed. But first, we had to get down this mountain.

I just about ran down. I wanted to get to the trailhead before dark – we’d have a much easier time getting a ride while there was still light. But, the sun beat us. By the time we arrived at the trailhead, everything had closed-up and it was dark. We were just about to give up hope when Donna managed to get a ride from a guy named Al. His was the only car we saw. I was happy to get the ride, but I stupidly left my gloves in the car… Doh! After getting a meal at the local diner, I split a hotel room with Donna and had a good night’s rest.

I had another lazy morning the next day. Donna and I weren’t good at getting eachother going. After buying a little extra food, we managed to get a ride to Independence from a Swiss man who was paragliding all over the US. Rough life. In Independence, we didn’t even have to hitchhike. A local woman saw us and figured we needed a ride. She asked her daughter to drive us to the trailhead. That was a real stroke of luck and kindness. At the trailhead, we started talking to a couple of guys who were getting ready for their own trip. They were going to study some rare mountain frogs at one of the lakes near the PCT. They had a pile of extra food which we happily raided. The hike back up Kearsarge Pass was a little easier than I expected. A good deal of snow had melted in the last few days, and the trail was fairly easy to find. It was still a long climb, up about 5000 feet. About 4 miles after the top of Kearsarge Pass, we arrived at the PCT again and were on our way.

We quickly reached the area of Glen Pass. It was another steep snowy mountain pass. We didn’t get there until early evening. I had been in this situation before, and this time I was determined to make the right choice. I decided to camp at the base of Glen Pass, rather than attempt to get over it before dark. The two hikers I was with, Sophie and Donna, went over the pass. I had a new attitude about the mountains after the events of the last week. Instead of trying to constantly challenge myself, I decided to take it easy. The mountains were enough of a challenge all on their own, I didn’t need to make them even tougher by pushing myself. Also, this was some of the most impressive scenery I’d seen in my life. I wanted it to last as long as possible. I had a pleasant night, and wished the best for Sophie and Donna.

The next morning, I got moving rather early (for me at least… 8am!). I made it down the other side and caught up with Sophie and Donna. They still hadn’t gotten out of camp at 10am. Apparently, they had a rough time coming down from Glen Pass the night before – it was steep and dark. But, they made it. Donna and I headed out with another hiker who had caught up to us, Little Bear. The walk north from the high valley of Glen Pass was beautiful, and the start of what would become a familiar routine. It went something like this:

1) Hike over the top of the pass.

2) Slide down the snow on the other side in the approximate location of the trail.

3) Walk by pristine, half frozen alpine lakes in a huge snowbowl/valley.

4) Hike down into the tree line.

5) Continue to post-hole through the snow among the trees.

6) Play “find the trail” – skip from bit to bit of thawed-out trail segments.

7) Hike down a steep canyon next to a raging stream which contains all the snowmelt from above

8) Enter a broad U-shaped (glaciated) tree-filled valley.

9) Pass by sections of grassy meadows, where the deep river winds and flows slowly.

10) Cross a big fat creek.

11) Hike up to the next pass in reverse order (Except that instead of sliding down, go up to the pass by the best route you can find… usually where the trail goes, but not always)

That’s just what we did on the way down from Glen Pass. This was a particularly pretty valley. Woods creek connected 6 good sized lakes into a clear cool mountain necklace of water. We got further down and the trail got soggy. But, I preferred mud to snow so it was OK. We finally crossed Woods Creek on a bridge. The trail then headed up the other side. We followed another fork of Woods Creek upstream. It flowed over solid granite slabs and often turned into a giant frothy cascade. By evening, we had made it up to the alpine area below Pinchot Pass. It was getting late, so we found a flat area covered in gravel and slept.

Little Bear left before the sun came out – I never saw him again. Donna and I barely started moving by 9am, but neither of us complained about it. It was damn cold in the morning shade. Once the sun hit us it would become bearable, and like a couple of cold blooded reptiles we’d start to move. I must have looked at the map 100 times on the way up Pinchot Pass. I wasn’t about to take another “wrong pass”, and Pinchot wasn’t too obvious. But, we finally figured out where to go, and made it up there. When we were near the top, another hiker named Lindy caught up to us. Lindy was from Minnesota. He passed us a couple hours later and we never saw him again. Although, we did hear a lot about him… he hiked long and fast. He was the 2nd or 3rd person to make it to Canada.

Heading down Pinchot Pass wasn’t so bad at first. Going downhill was usually easier than going uphill. I just enjoyed the views and trudged through the snow. The difficult part came later, during the “Continue to post-hole though the snow among the trees” and “find the trail” steps. The snow here was deep and soft. We’d sink into it a few feet with every step. The trail was nowhere to be found, and it was difficult to figure out exactly where it was by looking at landmarks. The trail went around a ridge, then switchbacked down to a fork of the King’s river. This last section was no better than the previous one. We just went through the woods, and followed the river until we saw the trail again. It took a lot longer than we’d hoped. We later met a couple of hikers who had been lost in this area for an entire day. Crossing the King’s River was the first time where we HAD to get wet. There weren’t any good logs or rocks to cross on. The river was only 1-2 feet deep, but it was moving swiftly. Our boots got completely drenched as we waded through the cold water. We took a break soon after, and were passed by a number of hikers that I’d never met – Shirt, Packrat, and a couple others. We called out to them, but they couldn’t hear us over the noisy stream. I never caught up to them.

The trail up to Mather Pass was wet. The snow in the surrounding mountains was in full melt-mode, and rivulets were everywhere – including on the trail. The trail made a perfect channel for the water, and there were many times when it was the biggest river around. We finally made it up to the valley before Mather Pass, and there was Fearless… reading a book and relaxing in the sun. He’d been watching hikers pass by all day and couldn’t figure out why everyone was rushing though this magnificent area. He convinced us to camp there. Mather Pass would be easier in the morning, when the snow was stiffer and a bunch of hikers had made fresh footprints. We were on the “pass-a-day” program, one of these mountain passes was enough for each day.

We were at about 11,000 feet. The air was clear and there was no moon. The stars that night were incredible. They had always been pretty good, but I remember this night as the best of them all. The entire sky was a rich creamy white – made from a billion tiny specks of light. Any familiar stars were washed-out by a background which set them in brand-new fabulous constellations. In every direction, the sky was full of them. The mountains which surrounded us were the perfect frame. Rugged, snowy granite walls pointing to the heavens above. I didn’t want to close my eyes and miss even one moment. But, sleep finally overtook me and morning came.

We got another 9am start. When I first met Fearless after Forester Pass, he had said “Hey, you’re doing well, you just made it over the second hardest pass of the PCT”. Second hardest? I had a rough time time on Forester Pass, but Mather Pass was rumored to be more difficult. From a distance, Mather actually looked pretty easy. It was very obvious, and a lot lower than the mountains which surrounded it. We walked a few miles over flat rocky terrain, and got to the base of Mather. I could now see that this was going to be a challenge. The switchbacks up Mather were completely covered in snow, and it was steep. To the left was a wall of snow and to the right was a steep granite boulder field. Most people had gone up the boulder field, but I decided to try the snow wall. I made pretty good progress at first, but after a couple hundred vertical feet the snow got so soft and deep that I was sinking up to my hips. I trudged over to the boulders. I had managed to get above the most difficult part of the boulders, and was able to get to the top without too much difficulty. It took a long time though. There were countless routes to choose from, and the best route wasn’t obvious. I didn’t want to get stuck halfway up and have to climb back down. Having a bulky backpack made it more difficult. My options for “slithering” up the boulders were limited. At the top, I took in the views and waited for Donna. We were just passing a German couple named Lucky and Pancake (or maybe they were passing us…). Pancake was feeling ill, and they were headed out at the next chance – Bishop Pass. Below Mather Pass, we spent a couple hours postholing through the snow and trying to find the trail. After going up and down the side of the mountain a few times, we finally located the trail. We cooked a quick meal and continued on. Ahead was an absolutely enchanting section of trail. Water was streaming down from the tops of the Palisades, some 4000 feet above us. Every space between the boulders contained a waterfall. Some of them were huge, some just a trickle. The trail dipped down to the shores of the Palisade Lakes, and then through a steep-walled canyon. All the water from above was rocketing through the canyon – it was a raging torrent. The steep canyon trail continued. At one point, the switchbacks were so tight that you could see the whole trail below. This section of trail was nicknamed the “golden staircase”, that name should give some idea of what it was like. We were headed down to a gigantic U-shaped basin which contained the Palisade Creek.

We had walked about a couple miles along the bottom of the valley when I spotted a bear. It was about 60 yards in front of me, just off the trail. Its head was down, rummaging through the mud, and it didn’t seem to be aware of me. I stopped, walked back out of sight and waited for Donna to catch up. “There’s a bear on the trail up ahead”, I calmly said to her. The look on her face was priceless – like a little kid about to meet Santa Claus. She fumbled for her camera, and we went back up the trail. The bear was still there, minding its own business. We took a few pictures and eventually the bear noticed us. It froze, stared straight at us, then started to walk our way. Seeing the bear was a treat, but I really didn’t want to “deal” with the bear. I looked at Donna “OK, now what?”. Donna clanked her poles together and the bear took off running (what a woos!). We made some more noise and he quickly scampered up the side of the valley. After hiking a few more miles, we finally camped next to the noisy yet peaceful Palisade Creek.

We had a long way to go to keep up with our “one pass a day” schedule. Muir Pass was about 17 miles away and most of that was uphill. So, we headed out. Along the way up, we were treated to some beautiful grassy meadows bordered by steep granite mountains. It was like an imaginary dreamland, but it was tangible and alive all the same. The mountains, the meadows, the bright blue sky, the sound of the wind and birds, the smell of everything fresh – it was a delight to the all senses.

We finally arrived at our “steep climb up a canyon next to a raging stream”. An avalanche had recently come through this area. There were huge boulders and shattered hunks of trees scattered on top of the snow. I couldn’t see how anything might survive this level of destruction. I looked up at the cliff where the avalanche had come from and I was thankful that it hadn’t picked this moment to do its work. Finally, we got up to the “alpine lake” section of the Muir Pass ascent. There was a ton of snow up there. The terrain wasn’t as steep, but it was miles of thick snow. Luckily, the snow supported our weight and we were able to walk on top of it (although every now and then we got surprised by a deep post-hole). The area around Muir Pass was just pretty. I didn’t have that same apprehension I’d had about some of the previous passes. I knew that Muir Pass was gentle, so I just enjoyed it. We had miles and miles of unspoiled alpine wilderness all to ourselves. We made it to the top of the pass around 4pm. Right on top there was a small stone shelter cleverly named “the Muir hut”.

It was built in the 1930s by the Sierra Club (which John Muir helped found). The area was enchanting and serene. The air was still, and there wasn’t a movement or a sound for miles in any direction. We looked down the other side of Muir Pass and saw an endless snowfield. We decided to spend that night in the hut. It would be a lot easier to walk on the snow in the morning, and besides, it was just a damn cool little hut. We unpacked our stuff and made ourselves at home. There wasn’t much in the hut – an empty fireplace and stone benches. It was perfect though, more than we needed. We got acquainted with the hut’s one permanent resident – a big fat marmot. He kept nibbling on our boots and even came inside at one point. We should have been annoyed, but he was so cute that we put up with him. We relaxed, cooked dinner, and waited for the sun to go down. It was one of the best sunsets of the trip. The whole western sky lit up. We got to watch the whole thing – a slow gentle peak of color, then a quick fade into the night. I slept well.

The next morning, we had to get moving. We inventoried our food and realized we had just enough to make it to our next stop… if we hurried. So, we started down the gentle snow covered north slope of Muir Pass. By this point, we knew the routine. We didn’t get too excited if we couldn’t find the trail. Eventually, we’d get low enough and the trail would reappear. That’s just what happened. We were headed down to Evolution Valley, and knew that our first difficult river ford awaited us at the end of it. All the melting snow from all the peaks in this giant long valley channeled into Evolution Creek, and we had to get across it. We walked through miles of forests and meadows, and finally arrived at the crossing.

I knew it would be a challenge, but at first look it seemed impossible. The creek was about 40 yards wide. It was at least 3-4 feet deep (I couldn’t really tell from the shore), and swift. To make matters worse, the water was bone cold – just above freezing. We scouted up and down the riverbank, but it looked the same everywhere. So, I sucked up my gut and decided to go for it. I made it halfway across without too much trouble. The water was up to my stomach, but I was still in control. Then, before I realized what was going on, I was floating – out of control down the river. I started to dog-paddle as best I could. I didn’t want to release my backpack (which would make it easier to gain control) except as a last resort. The cold water shocked my chest and all the air went out of me. I had just started to panic when I realized that I wasn’t moving too quickly downstream. I was headed for a shallower area. So, I waited for the river to take me there and I planted my feet back on the bottom. A few more hurried steps and I reached the opposite shore. I leaned over on the bank – cold and exhausted. I’d made it, and I knew I’d be OK. Donna was still on the other side though. She was shorter, and was likely to have more difficulty than I had. We started looking for a better place to cross. Once I warmed up, I tried crossing back to the other side at a different location. It was a lot easier – the water only got up to my thighs. It was still deep for Donna though – up to her waist. She decided to go for it, and after a bit more struggling we were both across. We were tired and cold, but downright proud of our little accomplishment. We’d done it! We warmed ourselves up with a hot meal and continued on down the trail.

It’s a good thing we didn’t know what was ahead. A quarter mile downstream, Evolution Creek turned into a huge cascading waterfall. It dropped a few hundred feet, crashing over boulders down to the San Joaquin River. We hiked until dark and camped near the river.

We only had one day of food left, and knew that we had to get close to our next stop by that evening. We still had one more pass to get over. Luckily, Selden Pass wasn’t nearly as formidable as the previous passes. The top of it was more of a narrow canyon. There was a lot less snow on the south side of Selden and we made good time.

The view north from the top of Selden Pass was spectacular. We’d hiked through plenty of amazing scenery already, but it never got old. I was greeted by more semi-frozen lakes, huge snowfields, and rugged mountain tops. We started down the snow. Along the way, I ran into a man who was up there fishing with some friends. He told me the trout were huge, easy to catch, and everywhere. They had more than they could eat. We had to keep moving though (If I had thought about it more, I would have stayed – fish is food, duh.). We finally worked our way down snow-covered switchbacks to a crossing of Bear Creek. This crossing wasn’t as bad as Evolution, but it didn’t look easy. We found a place downstream where the river split in two. It was a lot more shallow and we waded across.

Halfway across the creek, we found a new incentive to keep moving – mosquitoes. This valley was filled with the evil little bloodsuckers. Once we got across, we tried to dry-out our boots, but were quickly overcome. And I MEAN overcome. It was sheer misery. There was no escape. Mosquitoes don’t care if you kill them, there are always more… and more, and more and more. We danced around as we tried to put on dry socks. Anyone looking at us from a distance would have though we’d gone nuts – they wouldn’t have been wrong. Swarms of mosquitoes can do more than suck your blood, they suck out all the joy of being outside. All the greatness and grandeur of the PCT was gone in an instant. We scooped up our stuff and ran down the trail. The mosquitoes didn’t go away though, they came at us like a plague – following us down the trail. If we outran one swarm, they simply called their friends to pick up the chase. It sucked, they sucked, and I couldn’t get out of there fast enough. Finally, we started climbing up Bear Ridge and the mosquito crises abated. We hiked until dark and finally camped on top of the ridge. There was ONE good thing about mosquitoes, they did get us moving. We were only 6 miles from Edison Lake and the ferry ride to Vermilion Valley Resort.

The next morning, we ate the last of our food and trudged down to the ferry landing on Edison Lake. We were greeted by a sign which informed us we missed the ferry by a half hour. We’d have to hike about 5 more miles around the lake. We were already pretty hungry, and weren’t looking forward to this extra mileage. We had just started walking when we came across a familiar group of people. Jason, Lara, Charlotte, Arron and Sophie were all headed the other way, having spent the previous night at Vermilion. We swatted mosquitoes while exchanging stories of the previous section. I had hiked from the border on & off with all of them. I didn’t know it then, but it would be the last time I’d see any of them on the trail. They slowly got ahead, and I never caught up.

We had figured that the trail around the lake would be gentle and flat… the lake was flat, and the trail went around the edge of it. No luck. The trail had the last laugh, and routed us up 400 feet, down 400 feet, up 400 feet, down 400 feet till we were thoroughly pissed-off and wiped-out. I finally got to Vermilion and ate two lunches.

I had heard good things about Vermilion, and it was a pleasant place. But it also had a way of sucking money out of my pocket – $8 for a little tube of bug repellent, $15 for a meal, $4/minute for the phone… By the time I left the next morning, I’d run up a $100+ tab. It didn’t matter too much that my first beer and the bunk bed were both free.

We did catch the ferry back to the other side of the lake ($6 by the way). When we got back to the trail, I realized that I had a new problem. My stomach was tied in a knot. I didn’t know what was making me sick, but it wasn’t going away. As we climbed up to our next pass, Silver Pass, I started to have serious pains. The area around Silver Pass was one endless white snowfield, not a good place to be when I had a 5 second warning to find some privacy. I almost felt worse for Donna, who was putting up with me. I dragged myself up and over Silver Pass, then down the snow on the other side. I hadn’t eaten anything since breakfast, and I was running out of energy. I tried munching on some crackers, but I didn’t have an appetite either. I was on a downward spiral, and I didn’t know just how bad it’d get. I was a day’s hike from the nearest road, and I didn’t know if I could hike one more hour. After a day filled with short breaks and short walks, we finally made it to a flat grassy area north of Silver Pass. I plopped onto the ground. The lack of motion made me feel a little better, and by that evening I was able to eat some noodles. We had a choice to make: we could follow the PCT for the next ~25 miles through some swampy areas and then up a snowy ridge, or we could take an alternate route – almost the same distance, but down. The alternate had two difficult river crossings, but went by some hot springs. At this point, hot springs sounded better than snow, so we decided to take the alternate… tomorrow.

The next morning I felt a lot better. I was still sick, but I could tell I was on the way to recovery (later, I met a lot of other hikers who complained of the same symptoms coming out of Vermilion. All the sick people ate meat there. One of the hikers got sick while he was still at Vermilion. He said that Vermilion was quick to deny any possibility it was due to their food. I hope the problem has been addressed, getting sick in the backcountry can be a very serious matter.) We started hiking the alternate route – following Fish Creek downstream. We arrived at the first crossing of Fish Creek rather quickly. It was deep – above my knees, and very swift. I forced my way across and waited for Donna. She went about 10 yards and got stuck. The massive force of water quickly knocked her over and she got dunked. I helped her back to shore where she warmed up and had another try. Unfortunately, she’d lost one of her hiking poles in the creek (and wasn’t too happy about it). With a renewed determination, we both cursed the creek and powered our way across.

We took a short break to dry off and warm up, then headed on downstream. We knew we had to cross back over the creek further downstream – where there was even more water. Along the way, we kept an eye out for good locations to cross – where a tree had fallen over the creek, or where the creek got broad and shallow. Five miles later, we arrived at the second crossing. Helen was there with her dog. She’d been there since the previous afternoon, trying to decide what to do. She had arrived at the crossing with a few other hikers. They all had problems – falling over, getting soaked, nearly floating away… but they all made it over. The river was rather broad right where the trail met it, but the other hikers had picked a narrower spot 20 yards upstream. The “trail crossing” looked manageable (much like the first crossing, but longer), but there was a 10 yard wide spot on the opposite shore which we couldn’t see clearly. From our vantage point, it looked really deep over there. Helen had scouted the river bank all the way up and down. The “trail crossing” looked like her best option.

Donna and I had enough of getting wet. There was a fat tree across the river, about a half-mile upstream. We decided to try that instead. The tree trunk had snapped about 10 feet above the ground, and the tree was still attached to it. We had to climb up the trunk in order to get on the tree. With a little difficulty, Donna and I managed to do this. But there was no way Helen’s dog could get up there. We agreed to scout out the other side of the “trail crossing” when we got there, and yell to Helen if it looked OK. We got across the log and hiked through the woods to where the trail crossed the river. The “deep area” wasn’t deep at all, just a shallow eddy in the river. Helen came across.

Helen’s dog, Ceilidh (that’s pronounced Kaylie), was one of the most well mannered and smartest dogs I’d ever seen. She always knew exactly what was going on, and somehow seemed to understand the goal of hiking the PCT. Whenever I met Helen on the trail, we’d stop to chat and Ceilidh would whine – she wanted to keep moving! She’d been stuck on the other side of the river for a whole day, and when she got to the other side her joy was obvious. She ran full-speed in tight circles, barking and wagging her tail – the dog equivalent of “YAHOOOO!!!”.

Donna and I hiked about 6 more miles that day – just enough to make it to Fish Creek hot springs. These were some wonderful natural springs. They were 10 miles from the nearest road, perfectly warm, and all ours. We set up camp and relaxed in the springs under a blanket of stars.

The next morning, we headed further down Fish Creek, then up a ridge toward the Red’s Meadow area. Just before passing Red’s Meadow, we passed by Rainbow Falls, where one fork of the San Jaoquin river freefalls a good 40 feet. The mist of the falls created a semi-permanant rainbow near the base of the falls – they were well named. By this point, we were only a mile from the nearest road. People were suddenly all over, having their wilderness experiences.

I had mixed feelings about the day-hikers I saw. On one hand, it was good that they were out there. I was glad that people were here to see something as beautiful as Rainbow Falls. On the other hand, I had developed a nasty arrogant attitude toward day-hikers. I really didn’t want to have this attitude. After all, I had been a day hiker, and I hoped to be one again someday. But right or wrong, there it was. I’m still not sure what brought it on. Perhaps it was because all these people stopped at the falls – they didn’t have the drive or desire or time to go further. They dragged their soft bloated bodies the mile or so to the falls, called it a day, and felt like they’d connected with nature or something. There was so much more to see and do, so many more places to go. How could they just stop here? I eventually worked on my silent attitude, but it took a while. Life is infinitely more complex than any hike through the mountains. I had no idea who these people were or where they’d come from. I talked to all the day hikers I could. I found that nearly all of them were great people who’d lived interesting and full lives. Everyone is on a through-hike, sometimes it just doesn’t involve a trail in the mountains.

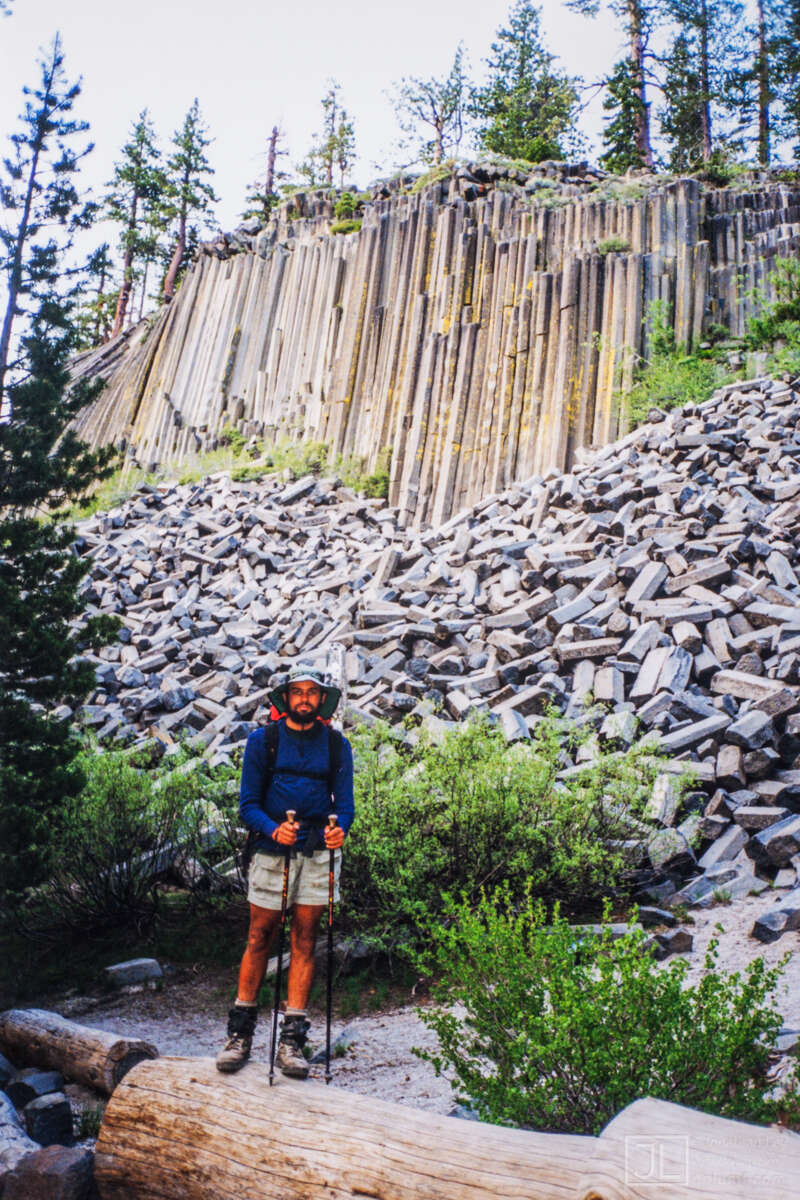

After Rainbow Falls, it was a short walk to Red’s Meadow, a small resort in the mountains between Rainbow Falls and Devil’s Postpile (our next natural wonder). I had a couple meals at the restaurant in Red’s Meadow and we headed out. After a short while we came across Devil’s Postpile. It was a neat formation of hardened lava. The lava had cooled into vertical hexagonal pillars some 50 feet tall. Some of the pillars on the edge had fallen over, and layed in a broken pile at the base. We had heard about Devil’s Postpile from everyone near Red’s Meadow. It was cool, but this one wall was it the whole thing – we had expected it to go on for a mile or something. I don’t know why, but we found the whole thing funny. We kept joking about how the next “natural wonder” couldn’t EVEN compare to Devil’s Postpile!

At dusk, we arrived at Minaret Falls. We had to cross the base of the falls. It didn’t seem too difficult at first, but the falls kept going and going. Before we knew it we were wet up to our thighs. It was still dark, and we couldn’t figure out how to get past the falls. We decided to camp on a small island which split the cascading water. It was incredibly loud – water was falling all around us through the trees as far as we could see. Still, even a loud waterfall can be peaceful. I slept fine.

We didn’t feel like starting out the day soaking wet. So, we decided to take a short alternate route around Minaret Falls. The alternate route passed by a series of car-campgrounds. It was Sunday, and the campgrounds were well stocked with people. The trail soon left “civilization” and climbed into the Ansel Adams wilderness. The whole area looked like an Ansel Adams photograph – steep black mountains, patches of white snow, and sparse trees popping out of granite hills. We stopped for dinner at Thousand Island Lake then kept hiking.

We passed a couple who were camped above the lake and asked if they had any information about the condition of Donohue Pass. “Oh, there’s a lot of snow up there. It’s really steep and could be dangerous”, he told us. I raised my eyebrows, tilted my head, and kept talking. He asked us where we were headed. “Well, we’re hiking the whole trail”. He smiled and corrected his previous advice, “Don’t worry about Donohue Pass then, you won’t have any problems”. It seems he had two sets of answers depending on who he met. We all had a little laugh about this, and parted ways.

We finally camped at a particularly pleasant spot. It was a flat grassy area on the side of a hill, just out of the snow. A small stream was flowing nearby, and huge trees were sparsely scattered about. We made a campfire, enjoyed the peace, and had a good night’s rest.

The next day, we headed up to Donohue Pass. The hike up was over gently sloped snow fields. The location of the pass was a little difficult pick out, but after numerous map checks we found the trail and made it to the top. Donohue Pass is the southern border of Yosemite National Park. The view north stretched all the way up Lyell Canyon to the Tuolumne Meadows area, about 14 trail miles away. That’s where we had to go, down the canyon and through the valley. It was a little tricky getting down from Donohue Pass, the trail was snowy and steep. But by this time, it was all old hat. We stopped for a break at a bridge going over Lyell Creek. I knew that the dining room at Tuolumne Meadows Lodge closed at 8pm. I had to cruise at over 3mph in order to get some dinner. So, I hiked as fast as I could down the soggy meadows of Lyell Canyon. This was the largest system of meadows I’d seen yet. The flat grassy valley bottom was about a quarter mile wide, and it went on in sections for 5 or 6 miles. Lyell Creek cut a deep smooth snakelike path through the middle of the valley.

I realized that this was an area in which John Muir had spent a lot of time. I was hiking on the “John Muir Trail” section of the Pacific Crest Trail (The JMT goes from Mt. Whitney to Yosemite NP, basically section “H” of the PCT). I had read some of his books before beginning my trip. The valley was just as he described. I could now see why his narratives included so many superlatives and references to God. The land here experienced time in eons. I was looking at some of the same living trees that John Muir had described in the 1870’s… some of them were hundreds of years old. The only direct evidence of man was the multi-tracked muddy path that I was slogging through.

As I got closer to Tuolumne Meadows, I saw more and more people. I didn’t stop to talk to them, just smiled, said “Hello”, and continued on my mission to acquire a hot meal. I finally made it, and the nice lady there let me have a seat (I was supposed to have a reservation) at one of the family-style dinner tables. I chowed-down my food and made small talk with the others at my table. Donna arrived a short while later. When we were leaving, we found a note at the front desk left by some people that Donna had talked to on her way in. It was rather cryptic, but essentially said there was an empty bunkhouse which we could use in the “government camp” area. We got to this sprawling compound in the dark and spent a good couple hours trying to figure out where to go. By 11pm, we finally arrived at what we thought was the correct bunk-house… it was empty anyway. We snuck in and slept on some soft beds. What could they do? kick us out? Oh well, nobody seemed to care (we never did catch up with the people who left the note). We spent the next day running errands and hanging out with some of the other hikers who were “in town”. There were a lot of new faces. While we were in Lone Pine, a number of hikers had caught up to us. We were among a whole new “crowd”.

By 2pm the next day, it was time to get moving again.