The plots of private land grew progressively larger as I distanced myself from Pie Town. After a few miles I was again walking past ranches the size of small kingdoms. Somebody had told me that it was legal to shoot trespassers in the state of New Mexico. While I doubted that, it was enough to keep me on the road. Even if it wasn’t actually the law, some locals might have thought it was the law, and that was all that really mattered. I imagined some crazed landowner was peeking at me through the dusty windows of his castle, clutching a rifle, just praying that I’d step on his land so he could “get one”. That kind of scenario would make any legal argument moot. I’d only been walking though the area for a few days, and it was nearly enough to drive me crazy… what of those who’d lived there for 5 generations? What degree of mental drift had they reached?

The landscape continued much the same as it had been north of Pie Town – scrubby trees and dried fields of grass. The only thing that kept my spirits up was the knowledge that the road would end… eventually. The land never stayed the same for too long on the CDT. I just had to be patient. I wandered off the road to a windmill, about 15 miles south of Pie Town. The wind wasn’t blowing, so I had to make do with water stored in an open tank. I did my best to filter from below the layer of dead bugs floating on top, and above the layer of decaying bugs on the bottom. While I sat nearby cooking a meal, a herd cows arrived.

The only drive more powerful than a cow’s fear of humans was its thirst. Cows were not a desert animal, and needed regular drinks to survive. I got a close-up look at them. They were disgusting creatures. Many had open sores on their necks that leaked puss and attracted swarms of flies. Their eyes were mostly bloodshot or glazed-over. I figured they were fairly blind. Their faces were covered in a mixture of snot, drool and dirt. Some of the cows sported grotesque mutations and growths around their facial features. Worst of all was the stench, a wretched mix of manure and bad breath. The cows spilled their drool into the water, and then clumsily lapped it up with their tongues. Occasionally they paused to let out a pathetic “moo”, or spill diarrhea from their backsides. Most of the cows had only to live long enough to gain valuable weight, their long term health was not important. Some were lucky enough to breed for a few years. Those fared slightly better and received regular doses of antibiotics. Although, I thought the luckiest of all were those culled for veal, spared the prolonged misery of their peers.

A few cars rolled slowly past as the day wore on. The mountains were gradually returning – rippled mounds, covered with trees. I passed through the northern boundary of the Gila National Forest. The Gila was an area larger than some eastern states, and one that I’d call home for the next week or two. I gradually rose up the flanks of Mangas Mountain a small but prominent peak covered in Ponderosa Pines.

I quickly grew to love the ponderosas, their bark was a smooth rusty brown, assembled in plates with black borders. The long ponderosa needles sung in the wind, making even the slightest breeze majestic. Beds of soft brown fallen needles, dropped slowly over decades, formed perfect beds below the older groves. I found a place to camp among one of them. It was far more soothing and medicinal than any mattress of springs and foam.

I continued over Mangas Mountain early the next morning, then began a long descent along little-used and nearly-forgotten forest roads. I began to hear the forest humming… or was it just my head? I realized the humming was from bees. The bees were everywhere, one every few feet. They hovered and swayed above the mat of pine needles, in a never-ending opportunistic search for anything different. I was often a target of their curiosity – brightly colored and covered with water and sweat, I was an oasis for the bees. I could never remain in spot too long without attracting at least a couple persistent buzzing companions – mesmerized by my face.

I reached a paved road by noon. I waited a while for traffic, then started walking west, toward Reserve, 40 miles or so down the lonely road. The first few cars passed by, one every 10 minutes or so… Then a pickup stopped, the bed was loaded with freshly cut wood. Before I had a chance to get inside, the driver told me to grab myself a coke from the cooler in back. He was probably 55 years old, and owned a nearby ranch that had been in the family for over 150 years, back in the era when the area had been considered part of Old Mexico. “You know”, He told me, “most people around here won’t pick up hitchhikers, they still think everyone’s a hippy.” It seemed that things there changed not with months and years but with decades and centuries. He pointed out small plots of green land along a nearby river, “Those all used to be subsistence farms, but now they all just ranch cattle.” He seemed sad about that. Ranching was easier than farming, and people had naturally drifted toward it. They now hired ranch hands, bought their food at the grocery, sat at home and watched televisions. Progress. We passed a few groups of mobile homes. “Those used to be ranches”, he lamented further, “but the parents died, and the kids just split it up and sold it.” His ranch seemed destined for the same fate, his kids had gone to college and now lived in Alburquerque. He seemed sad about the way things were going, but resigned to it all the same. Who could define a good life anyway? Who was to say things weren’t getting better instead of worse? He twisted open a bottle of budweiser and flicked the cap out the window.

Reserve was an island surrounded by massive ranches and national forests. It was over 100 miles in any direction to a larger town, and I estimated less than a thousand people lived in or close to Reserve. Many of the locals guessed there were about 600. I picked up some groceries, then got a pizza and a room at the pizza/motel place near the end of town. I met a couple young men who worked for the fish and game department, they gave me an old map of the Gila National Forest. That evening, the Saddle Mountain Band played in the pizza parlor – 100% country, the only band in town. I was tired of it all.

The next morning, I hit the grocery store again to pick up a few things I’d forgotten. I packed my things together outside the store, both apprehensive and excited to leave Reserve. It was so easy to stay in a town, I didn’t have to carry anything, didn’t have to walk anywhere, and had plenty of opportunities to meet people. But, those were the same things that made me want to leave. Easy living had few special rewards and quickly lost its appeal.

An older gentleman noticed my backpack, and after a brief friendly conversation, offered me a ride back to the trail. He’d spent some time in the Navy, and was a former sheriff. Now, he spent part of the year working at the fire lookouts in the national forest. “It’s a pretty easy job”, he joked, “you just have to look out the window”. We shared a love of mountaintops. “People just don’t realize how special it is on top of a mountain.”, he told me, “I thought about retiring full-time, but what for? I’d rather sit in a fire lookout than in front of a TV.” We reached the ‘trail’, an old two-track road about a mile from the divide. I hoisted my water-laden pack and headed south.

The two-track quickly became a mere suggestion. I headed through waist-high grasses, made brittle by a summer of blazing sunlight. It was mild now though. In fact, it seemed that I’d picked most agreeable season to hike through New Mexico, halfway between the intolerable heat of summer and the cold dreariness of winter. I noticed a dark form running at me from under a bush. I was shocked, but recognized it immediately – a havelina. The havelina was a small wild pig, about 1.5 feet tall and 2 feet long, with dull brown horizontal stripes. Like every small animal, I’d heard it was “pound for pound the fiercest critter alive”. It seemed to be living up to that reputation. It snorted as it ran toward me, then took a 90 degree turn and bounced up and down, visibly upset, jumping full body lengths into the air as if it were on a trampoline. I couldn’t help but laugh. Then, I realized what had brought on the display of bravado. A whole family of little piglets scampered out from under the bush and ran in nervous circles. They were accompanied by a few slightly larger havelina which tried their best to reign-in the confused youngsters. The whole extended family slowly bounded away, snorting in protest through the bushes.

I crossed a couple miles of private property. Every large ponderosa was only a stump, they’d all been turned into cash by some rancher – “working” the land as if it were broken. I then crossed a barbed-wire fence that designated the boundary of the national forest. While I took a break under some still-standing ponderosas, a white pickup drove along a ranch road that bordered the fence. The people inside stared at me, as if they were sorry they’d missed my little trespassing episode. They spoke with their eyes, “We’ll get you next time…”

I walked through the woods, following only my compass, and the upward grade of the ground which led to the divide. A logging road was routed along the divide. It wasn’t on the map, but it headed the general direction I wanted to go. The road slowly drifted off the divide, then forked, then forked again, then bisected another road. There were roads everywhere. I did my best to keep heading south, but was continuously led in other directions by the roads. The roads didn’t head to any particular destination, they were only designed to provide access for logging vehicles. The windier the road, the more trees it passed, and the more money the national forest got. After a couple hours, it seemed like I was going in one big circle. “Enough of these damn roads”, I thought. I headed into the trees, back up a hill toward the divide. On the way, I passed more roads. At one intersection, I passed a large metal sign. Once a detailed map of the area, it was now bleached a solid dull grey by the sun. The only thing legible on the sign was a small label in the middle that indicated “you are here”. Just as I had figured… I was in the middle of nowhere.

I reached the divide again. There was no more road along the top, but somebody had cut blazes into the trees every 50 yards or so. It was the officially designated CDT. It seemed to be a joke. There was no trail, just loose pumice that twisted my ankles with every step. The blazes marked the divide, but the divide didn’t need any marking as it was the top of an obvious ridge. I thought about all the miles and miles of roads below… How much work had it taken to build them all? How many millions of dollars had been spent? And all of it just so a few people could cut down the trees and make a profit. Then there was the trail, not even a trail. There was no money to be made by building a CDT. And to those who made such decisions, there was no value other than money.

The divide dipped down to another road, one that was actually on the map. I was just below John Kerr Peak. About halfway to the top of the peak, I realized it was not where I needed to go. But, I was always a sucker for another mountaintop, and it was only a 30 minute detour. From the top of the peak I had a view south to miles of rolling forested hills and mountains that grew progressively higher and steeper toward the horizon. I was looking into the heart of the Gila, hundreds of miles of rugged land that once harbored the Apaches – some of the last American indians to be conquered by the white man.

I came down from the mountain, and followed the road to intersect another trail on the divide. It was a little better than the previous trail – there was an actual path – but it was in a state of prolonged neglect. Without either more foot traffic or more maintenance, it would soon be gone. I found a flat spot under the ever-present ponderosas and set up my tarp. As I slunk into my bed of ‘feathers’, a late evening thunderstorm opened overhead. But even the loudest racquet of raindrops and thunder was a melody that soon had me dreaming.

The trail gradually deteriorated after a couple more miles. After a while, it was nothing more than old blazes and a tangle of prickly dried plants. I decided to walk a road instead. The road also passed a couple water sources, which were something I needed to pass. The first of them, Dutchman Spring, was nothing more than mud, stomped by cows. A few miles down the road, I came to another ‘spring’. A pipe carried a steady stream of water from an unknown source to an open-topped holding tank – more water for the cows. I sat by the spring and cooked a meal, while a steady stream of hunters drove down the road on ATVs. It didn’t look like they were really serious about the hunting… though they appeared to be serious about drinking beer, riding ATVs, shooting guns, and dressing up in camouflage.

The road passed under some of the largest ponderosas I’d seen. The trunks had a diameter of 4 or 5 feet. The tops towered 60 or 70 feet into the air, gently swaying against a rich blue sky. The trees gave way to a large open plain of short grass which I cut across in order to save a few miles. I then followed a road back up to the divide. Along the way, a truck carrying 3 old hunters passed by me. “Need a ride?”, they asked. I politely turned down their offer. A few miles later I reached the divide and passed the hunters again, they were parked off the side of the road. “Geez, I didn’t think you’d make it up this far till after dark”, one of them commented. “Well, I’ve done a lot of walking”, I explained, “I’ve worked up to a pretty good pace.” I explained where I was heading. The man knew the entire Gila National Forest by heart it seemed. He mentioned that he’d hiked down the Gila River canyon “about 30 years ago, I think… Boy, it’s a beautiful country down there”. He shook his head and pursed his lips, then let slip a great secret, “You’re gonna live a long time”, he told me. I felt I already had.

Further up the road, I passed a section of forest that was undergoing a controlled burn. The bed of needles under the ponderosas was black and smoldering in places. The big trees were charred at the base, but generally un-phased. The forest looked empty, like it’d just been cleaned and swept.

At sunset, I left the road and came to another giant plain, soft rolls of grass extended for miles ahead. The sky ignited into a deep blue canvas painted with huge splotches of red and purple. A few pronghorn floated over the grass in the horizon. As darkness took over, an owl skirted past my head without a sound. For a moment I forgot where I was… I wasn’t hiking, I was just watching a movie and it was time for another intermission.

The frozen void of space clamped down that night, and I awoke to an icy landscape. We were so dependent on the sun for everything, always one rotation away from an inexorable deep freeze. If anything did deserve our worship and praise, it was the sun – the giver of heat and sustainer of life. I said “thank you” to the sun as it came over the horizon and melted the cold away.

I continued walking over the giant rolls of grass until they gave way to a series of snake-like canyons that grew fatter as they wound downhill. I reached one canyon’s bottom and observed a trickle of water steadily flowing from pool to pool. I’d be following that water for the next 4 days as it carved a path through the rock toward an ocean far away. It was an unofficial and inauspicious start of the Gila River.

First though, the water got trapped by a man made lake, Snow Lake, born in 1967. A nearby sign boasted how construction of the lake was financed by revenues from fishing licenses. I was almost surprised some corporation hadn’t bought the naming rights. A car-campground near the lake sported a population of outdoor motorsportsmen newly roused and stoking morning fires. I laid out my frosted belongings on a picnic table and munched on some nuts as a giant RV drove past. One man drove the RV, which towed a pickup truck that held an ATV in its bed – a progression of motorized distractions that helped keep his physical activity to a minimum.

A woman drove up. She worked for the forest service and managed the campground. She lived in a cabin somewhere out in the nearby woods. She got paid almost nothing but had no expenses. She seemed to be one of the happiest people I’d ever met, she’d found her nirvana, a route to happiness that didn’t require a bank. She’d met a couple CDT hikers in the springtime, headed north. From her description, I deduced they were the two I’d met up in Glacier, the two that had quit. I now viewed them in a new perspective, having seen what they’d missed. I felt sorry for them, I regretted not trying harder to encourage them to continue. I hoped the path they’d chosen had been the right one for them. I knew the path ahead was the right one for me. I walked around Snow Lake, over the earthen dam at the end, and down to the water flowing below. A mile later, I hopped over the Gila River for the first time.

I’d been looking forward to the Gila River since I’d crossed out of Colorado. It had been described to me as the highlight of New Mexico. And there it was, in front of me. The trail continued along the side of the river through a wide canyon of grassy meadows and ponderosa pine. It seemed so improbable that the river was even there… all that flowing water surrounded by so much dryness. Where was it all coming from?

The trail crossed the river periodically, and for the first 11 crossings, I was able to avoid getting my feet wet. After that, I splashed through cool ankle-deep water. The canyon was wide enough that I wasn’t always able to see the water. I began to look forward to the crossings, “Ah, there you are again…”, I’d say to the river. It just kept marching downstream. “Where are you going?”, I’d ask. It just disappeared around a corner, ignoring me. I didn’t mind being ignored though. I was like the little kid who loved his grandpa unconditionally, for no reason other than who he was.

On crossing #25, I slipped on some slimy rocks and fell into the water. I cursed myself for being so careless. The canyon was slowly changing, the walls were closing in and growing taller. The river was becoming more intimate. I was no longer ever removed from its soothing trickles and splashes. I stopped to eat at crossing #33 and noticed a bug crawling on me. It looked exactly like a seed of grass, complete with a frayed edge and leafy texture. What an amazing thing, I thought. How many generations of trial and error had it taken to get that way? Everything was so amazing, our little human history of wars and gadgets seemed so small.

By crossing #40, the canyon was so steep, it was past vertical. It was so tall I couldn’t pinpoint the top. I was walking down a slot in the earth, a sculpture in progress, made by nature with tools of water and gravity. Every crack in the rock was worth an extended observation. I finally camped just after crossing #57, under an overhanging cliff of volcanic rock that ended in pointed spires reaching to the sky. I made a campfire for the sheer pleasure of it. It was the proper place to have a campfire, a place that was like a home with two walls, running water and no roof… a secret passageway that was all mine.

I awoke to a martian landscape. The only light that filtered into the canyon was that reflected from the clouds above. The low rising sun lit up those clouds a bright red. It felt as if I was wearing tinted glasses, nothing escaped the red glow – the rock, the trees, the water… even my skin looked alien.

The volcanic structures above grew more elaborate and bizarre each time I crossed the river. I shook my head in disbelief that they were actually there, that it was actually possible. The sharply pointed pillars were a field of colossal inverted spikes, towering hundreds of feet, one next to the other. Each step revealed more columns and cracks and structures, more detailed topography than my overcharged brain could process. It was as beautiful as one could imagine hell without the fire and demons.

Around crossing #68, I heard a scream from above. A giant bird swerved through the canyon, just overhead. It was a bald eagle, and it appeared to be on a purposeful mission, flying faster than just to move from place to place. Seconds later another eagle followed, it had a large trout writhing in its grasp. Another eagle, perhaps the same as the first, came from nowhere, and made a daring grab for the fish. The two birds shrieked wildly and locked talons, spiraling out of control and out of sight behind some trees. It was a spectacular display of grace and power that befit the dramatic setting. It became another memory which reminded me why I was hiking the trail.

After crossing #89, I reached an area called “the meadows”. It seemed a rather kind moniker, as the trail disappeared into a mess of tall prickly grasses, muddy swamps and fallen trees. I wasn’t concerned though, the trail followed the river, and the river followed the canyon. All I had to do was keep heading downstream. A couple crossings later, I regained the trail and took a break. I had rarely felt so alone on the trail, and yet so at peace. I felt more at home, in the bottom of that canyon, than I had at any other place on the trail. Mountaintops were wonderful no doubt, but their attraction was stark and foreboding, they were no place to linger. Down in that deep canyon, next to that endless happy stream, I felt time slow down, and only felt a momentary sadness when some small element of my mortality betrayed the pacific illusion.

At crossing #124, I found a place where the illusion was real. A torrent of water, warmed by the weight of the earth, gushed out the side of the canyon. Someone had built a wall of rock and soil that trapped the flowing water into a pool colored as the sky. It was Jordan hot spring, and it was all mine. I trembled, and nearly cried for delight. I had seen hot springs before, but Jordan was so glorious and so unexpected, it caught my expectations off guard. I set down my pack and surveyed the scene. The pool was about 15 feet in diameter and 4 feet deep at the center. The water was like a warm bath, not too hot, but enough to arouse my sensations. The spring was shaded by a giant ash-leaf maple, a striking tree with smooth white paper bark and pointed leaves painted red, green and yellow. A great stem of the tree shot out of the canyon wall, horizontal, a few feet above the water. A few of its leaves floated on the surface in a lily pad decor. A team of giant red dragonflies rested on a twig that hung over one corner of the pool, a perfect final touch to an already idyllic paradise. I stripped off my clothes and sunk in the water, my toes dug into the clean sandy bottom and I let out a sigh that lasted 10 minutes. I floated there, naked, and felt the reversal of an old slogan, “feel comfortable to make yourself free”.

I spent the next three hours at the pool, allowing its presence to guide my every action. I rinsed all my clothes, I took another dip, I cooked a meal, I took another dip… I wished only that I’d planned things better. It was 2pm, and although I was tempted to stay the remainder of the day… if not the remainder of my life… I still had a trail to hike, and an unknown number of miles to my next destination.

A few crossings later, I passed a young couple. They were headed the other direction, headed for the hot spring. I was still delirious from its charm, and from the charm of the canyon, and the trail, and the sun, and the eagles… My overtones of joy likely made my speech incomprehensible, I think I told them it was 7 more crossings to the pool, and that if they weren’t already in love, they would be soon.

The canyon continued to grow in scale: bigger walls, deeper crevasses, and a height I could not properly perceive. After a couple more hours though, it slowly began to change. The volcanic rock gave way to a more familiar sedimentary structure – horizontal bands that told the slow story of time. The tightness of the canyon eased into a large hyperbolic curve. I walked forward, accepting each turn of the trail and each crossing of the river as perfect.

I spotted a cave, high up the canyon wall. As soon as I’d spotted it, I wondered what it was like, and as soon as that happened, I wondered if I could get to it, and then I found myself walking toward the cave thinking, “this is stupid”. I pulled myself up through steep loose gravel and stiff guardian bushes, I rammed my knee into a cactus. I didn’t care though, I was still on a high, and only a serious catastrophe would have brought me back down. The cave was nothing special, no broken indian pots or mystical writings on the wall, only some twigs, laid out in a pattern that spelled 7-11-01. Somebody else had been lured to the place, I had a good private laugh.

I finally called it a day after crossing #157. The day ended as it began – the world turning to red as the setting sun lit the sky.

The river was cold in the morning. My feet numbed with each crossing, then slowly came to life just in time for the next. The canyon grew broader, I wondered if it would disappear altogether. I heard a loud rustle in some bushes nearby, then saw a black bear running away from me, terrified, up the base of the canyon wall. I hadn’t seen a bear in hundreds of miles, in fact I’d almost forgotten they were even out there. I was happy to be reminded.

At crossing #166, I passed another hot spring. The water was very hot, but there were only a series of small ankle-deep catch-pools. I soaked my shoes in the water to revive my feet, then walked through the chilly Gila again, now almost 2 feet deep and 20 feet wide. Two more miles and two more crossings brought me to the Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument.

I went to the visitor’s center to pick up a package I had mailed c/o general delivery. The woman behind the counter was exceedingly nice, and in the kindest of terms explained they were no longer allowed to hold packages for hikers. It seemed that someone somewhere had mailed some anthrax to somebody, and the whole country was having paranoid delusions. I made some offhand remark about how people had gone more insane than I had, and one of the employees joked, “Well, you could always just keep hiking into Mexico…” “The thought has crossed my mind”, I quickly replied. Luckily, the visitor’s center was run by “real people”, and they had held my package. “Just don’t do it again”, they suggested. I promised to comply.

I spent an hour looking at every display in the visitor’s center. I watched a video presentation about the nearby cliff dwellings, it was nicely done. I bought a book about the Gila River. I sat outside and met a nice family from back east. “What’s your base weight?”, the father asked. He had obviously spent a lot of time hiking bits of the AT in order to come up with that bit of lingo.

I walked down the road to the cliff dwelling site. I stopped at one point to guide a tarantula off the asphalt. I lightly pushed the slow spider with my pole, and he reacted like a proud old New Yorker, “I’m doin’ the best I can, now back off!!!”. I arrived at the entrance to the cliff dwelling site, and explained to a very understanding man working at the entrance, that I had no cash to pay the $2 entry fee… only a credit card. “That’s OK…”, he smiled. He seemed to simply want everyone to have a good time. In fact, all the workers I met at the Gila Cliff Dwellings were incredible. They were the most genuinely happy and helpful people I’d met in a long time. I had to think that if I were working in such a place, I’d be happy too.

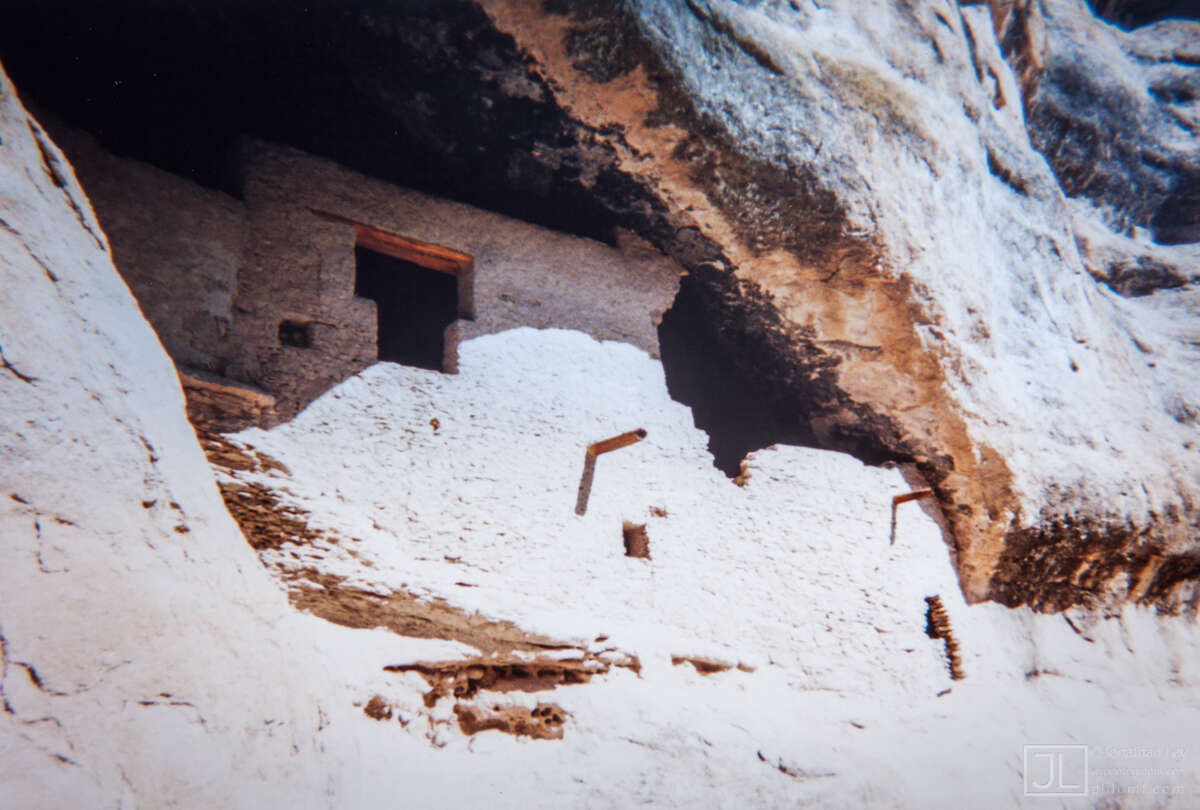

The actual cliff dwellings were striking and unique. They were the only cliff dwellings thought to have been built by the Mogollon indians. The Mogollon usually lived in adobe huts, but they did trade with the Anasazi – the tribe that had built the more famous cliff dwellings far to the north. It was estimated that about two dozen individuals had lived at the Gila site for a period of 20 years in the late 11th century – a short tenure by any standard. The caves themselves were shaded and cool, they faced south above a small reliable stream. In the caves were a number of chambers, subdivided by brick and mortar walls. I could almost see the simply-dressed inhabitants, happily going about their daily routines – mothers caring for babies, grandfathers sitting cross-legged, telling stories to children… a hunter returning from the mountains with a butchered havelina… What could have brought that community to so sudden a collapse? All of the cliff dwellings in the southwest had been abandoned around the same time. The going theory was that a horrible prolonged drought made their agricultural lifestyle impossible… but had it dried up the Gila River? Of one thing I was certain. The Mogollon Indians hadn’t left voluntarily. The place was far too perfect a home for anyone to have left it without a struggle.

While touring the cliff dwellings, I met a retired couple from California. They invited me to lunch at a nearby picnic area. They were nearing the end of 2 month road trip, one that had taken them to many of the places I’d walked through. For a short while, I almost felt like I’d met a second set of parents. They wouldn’t let me stop eating, which was not really a problem. After lunch, we said our good-byes and I hit the road. I walked past a nondescript wall of rock about 15 feet high. Something caught my eye. It was a simple petroglyph, an outline of a human hand. It wasn’t left by the Mogollon, it was older, left by people simply called “the ancient ones”. There were other similar petroglyphs in the area, but this one had no parking lot and no guidebook description, I felt it was a message directed solely at me, “I was here”, it said, “don’t forget me”. And they say that America has no history.