Click here to go back to Part 1

We had a pleasant evening and night at Washakie Lake. The surrounding area was a parkland – meadows interrupted by clumps of trees and piles of rock. This was a large and popular lake – with at least 4 or 5 other groups camped nearby. The forest service had even installed a ‘bear box’ nearby – a large metal chest where we could safely store our food. This saved us the trouble of hanging our food. While a nighttime visit from a bear would be a dramatic event, a more practical concern was protecting our food from much smaller nighttime critters – particularly, mice.

The next morning, we ascended toward Washakie Pass and passed a familiar progression – the last of the trees, the alpine meadows, an upper lake set in a bowl of rock, and the wind steadily building. But the wind was building less every day. Higher atmospheric pressure was bringing clear skies, calmer winds and warmer temperatures. The small alpine flowers were blooming in abundance as we neared the pass. Moths and butterflies fluttered between them, acting as flowers of the animal kingdom.

Butterfly and Moth identification is not one of my strong suits. But thanks to a network of experts and enthusiasts back home including Bob O and Sandy L, I was able to get them identified.

The Greater Fritillary was one of the more common species.

This is a Common Alpine (Erebia epipsodea), but I can’t honestly remember if these were common or not during my visit.

This is a Great Tiger Moth (Arctia caja), hanging-out on the leeward side of a rock at nearly 11,000ft.

I had been keeping an eye open for one particular bird I knew lived in this environment, and one which I was unlikely to have another opportunity to see for some time – the Black Rosy-Finch. Whenever our path traversed alpine slopes, I periodically stopped and carefully scanned. But this was a difficult time of year to find most birds. They were generally done breeding, so were not singing or being flashy. High summer was the time of year for them to simply survive.

Finally, just below Washakie Pass, my patience was rewarded as a few of these enigmatic birds made an appearance. They nest in such inaccessible locations – high elevation cliffs and among jumbled boulder fields in the alpine spring – that only 3 nests have ever been studied. As with most of the birds I encountered, these were in some stage of molting, and not quite as boldly-patterned as they can sometimes be.

The trail descended from the pass giving us new views of mountains further north, such as Mt Geike (to the left) and Raid Peak. This was as far north as we’d be hiking, from here our route turned south to ultimately complete our loop.

Halfway down from the pass, we spotted a group of Mountain Bluebirds, hunting butterflies from the branches of standing dead trees.

The views of surrounding mountains continued, framed by lakes and trees.

As we turned to start our next climb up the Shadow Lake trail, a woman passed us at a furious pace. She introduced herself as Kelly Halpin, and explained she was in the middle of an attempt at a new record “Fastest Known Time” (FKT) of the Wind River High Route. Her route traversed the entire Wind River Range near the crest, wherever navigable without specialized gear. At the point we crossed paths, she’d been going non-stop for 38 hours, and had up to 12 more to go. I’m not sure how she fared in her attempt, but we were impressed with her energy. Hopefully, she didn’t miss her goal by 90 seconds – about how much we slowed her down.

We next crossed the broad meadow of Washakie Creek with a fortress of high peaks all around.

The trail led us to the deep clear waters of Shadow Lake, where we made camp among the boulders just above.

While I was helping search for a suitably flat place to make our camp, I took off my pack and explored around the menagerie of boulders, forest and undergrowth surrounding the lake. There was a scarcity of flat earth; something was growing or jutting from everywhere I looked. Suddenly, without warning or witness, I stubbed my toe on a rock. My center of gravity was thrust forward and I found myself uncontrollably flung into fate. Before my tired mind could start to process what was happening, I landed on my shoulders, rolled heels over head, and landed… completely vertical – as if nothing at all had occurred. Somehow, in this place filled with granite boulders of all sizes, broken bits of trees pointed like spears, surrounded by an abundance of steep drop-offs, I managed to find a soft person-sized bit of earth to catch my fall and bring me back upright.

This seemingly minor episode could have gone so horribly wrong. There’s an inherent danger of being deep in the wilderness, a day or more’s walk from the nearest road. A small accident can quickly cascade into a crisis. I looked around at a scene unmoved by my tumble. “Did that really just happen?” I asked myself. From that point onward, I exercised a greater degree of both caution and humility. Fate let me continue on the journey, and I didn’t dare test it again.

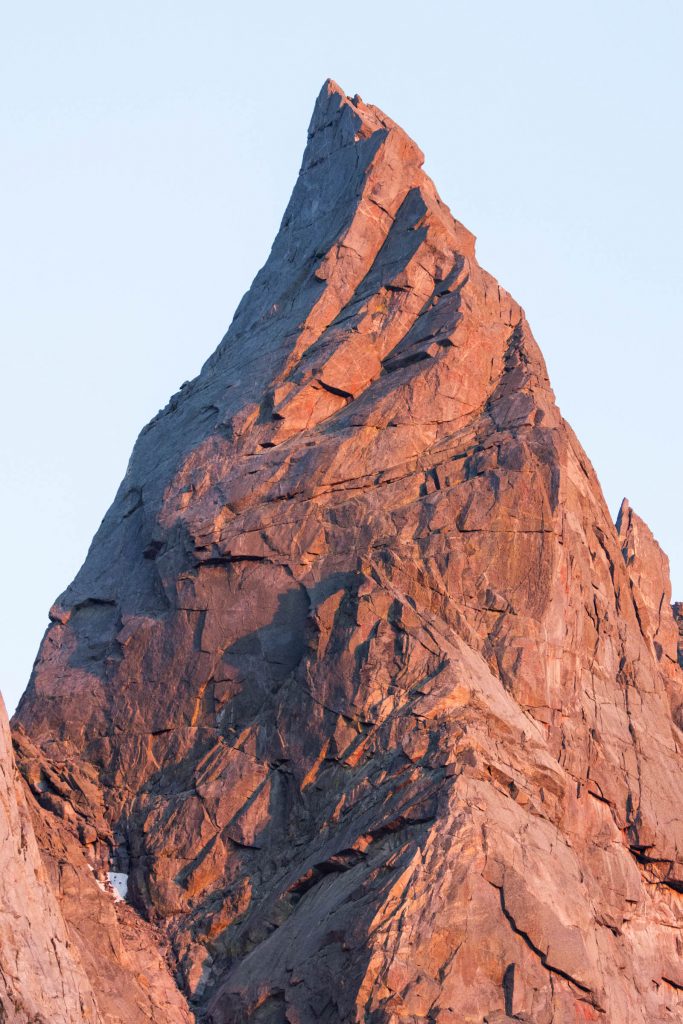

Our eyes were drawn to the pointiest of these sawtoothed peaks – the Shark’s Nose. This spire is more well-known from the other side, where it forms a part of the cirque of towers. From this side, the setting sun emphasized every crack and ridge. I wondered, how many people had once stood atop it?

I “cowboy camped” that evening – no tent, just the canvas of infinite sky. The Milky Way crossed from one horizon to the other, reminding me of my place in the order of things. I wasn’t even a speck.

The next morning, we continued up beyond the end of the officially-maintained trail, passing a couple more sparsely-vegetated lakes set in granitite bowls.

Texas Pass is a place I’ve long known about, but only second-hand. Finally, I had a personal introduction. The route twisted up a pile of rock – bits of tread appearing and fading-out. If you look closely at this image, you can see Loren and Joan along the shadow-line to the left side.

As we rested on top of the pass, a couple hikers arrived from the opposite direction. “Beer Man” and “Chukar Bird” were in good spirits. They had been walking for months from the border of Mexico to reach this point, close to 2000 miles so far. Texas Pass is a popular alternate route of the Continental Divide Trail (CDT) – a continuous hiking route of 2800 miles following the the spine of the Rocky Mountains from Mexico to Canada.

I hiked the CDT myself in 2001. The views from the trail haven’t changed much in the intervening 23 years, but the culture of the CDT has grown considerably. By my count, 16 people hiked the entire CDT in 2001. 600 began an attempt in 2024. Over those years, I’ve kept a connection to the CDT by publishing a set of printable maps of the entire route. Though most hikers have now migrated to navigation by app and GPS, my maps are still part of the conversation. It was especially rewarding to meet a couple hikers on the trail, in a place like this – one of the highlights of the entire route – keeping the CDT alive by living their dreams.

We headed back down the other side toward Lonesome Lake, and into the heart of the Winds.

We took in one of the most spectacular mountain views in the country – we’d reached the Cirque of Towers. Technically, the Cirque of Towers is a smaller upper cirque above Lonesome Lake, below a particularly jagged group of spires. But this entire upper valley around Lonesome Lake is typically called by that name. Everywhere we looked was an exercise in jaw-dropping.

After a long break on a shady log just above the lake, we continued our journey – out of this magical valley, and over the whimsically-named Jackass Pass. I was thrilled to encounter another group of Black Rosy-Finches.

From here the trail smacked into a pile of granite boulders the size of trucks stacked haphazardly on a lakeshore. We scrambled up and through them. The trail fell and rose and fell again – routed where the land allowed. I spotted this Brook Trout in a trailside pool, unaware of the twisting foot path above.

Our destination that evening was the far end of Clear Lake. We found another quiet bit of flat earth in the forest where we took off our packs and rested. A stream flowed over giant slabs of granite nearby, gathering in a series of pools. I found a good location to methodically cleanse my clothes and my body.

As I was quietly finishing a welcome meal of re-hydrated noodles and sauce, I was shaken to my senses when a large rabbit ran full-speed into the center of our camp. It had white feet – a Snowshoe Hare. In all my time in the mountains, I’d seen countless tracks of these animals, but had never seen the animal itself. They’re excellently camouflaged, and mostly nocturnal. But there one suddenly was in front of me. The hare had been running so fast, it knocked over a bowl, then looked at me, and ran full-speed the same way it’d come. I let out an involuntary “hey!”, and it was gone.

I cowboy camped again that night, mostly because I was just too tired to put up a tent. A couple hours after darkness took over, I heard a crunching sound coming from near Loren & Joan’s tent. I looked over as Loren turned-on his light to illuminate a Porcupine, inches from his head, chomping on his boots. The spiny creature lumbered away and into the darkness.

After we started our hike the next morning, we discovered some climbers had started their day even earlier. They were making steady progress up the walls of Haystack Mountain.

Beyond Clear Lake was Deep Lake. And beyond that rose Temple Peak. Our next destination was just to the left of it – Temple Pass.

As we climbed up the steep loose slopes leading to Temple Pass, we had splendid views back toward Temple Lake below, and seemingly endless mountains beyond.

The flowers along the way to Temple Pass were as bountiful as everywhere else. These clumps of Sky Pilot were especially attention-grabbing.

We took a break at the top of the pass, pondering just where the trail was supposed to be routed below. A Green-tailed Towhee appeared on top of a rock, looking especially raggedy. It let out a soft whistle before disappearing from view. It was the only one we saw the entire trip. You never know what’s going to be around the next bend or on top of the next rock.

The trail down from the pass started out very distinct… until it wasn’t. We were left to find our own way down, and drifted apart, searching for where the trail would re-emerge. We weren’t worried though – we knew were we had to go, and there were countless routes to get there. A few miles on, we found ourselves in a broad valley, where the river widened into a network of snakelike streams and ponds, good habitat for Spotted Sandpipers.

At the end of the meadow, our map indicated the trail hugged the western shore of Little Sandy Lake just ahead. But the trail disappeared as we continued along. It seemed to re-appear at moments, but then, false alarm – just more untrammeled wilderness. Still, we pressed ahead, the trail just had to re-appear. We reached Little Sandy Lake, and where the map indicated a trail, all we found was a steep slope of boulders and dirt. Still, we continued along… now perhaps resigned to the fact the trail was not here. But where was it?

After pulling ourselves up and over some rather precarious terrain, I stopped to consult my own maps. The printed ones I’d been carrying with me. Here I was, the “CDT map guy”, confounded by a missing trail, and neglecting my own work – and literally ignoring my own advice. Sure enough, the “Ley maps” indicated the trail was a quarter mile to our west, above and beyond the cliffs we were scrambling through. We found a notch leading us to the top of the ridge, and made a straight shot west. In a few minutes, we busted out of the forest and back onto the trail.

Only minutes later, we were passed by two groups of CDT hikers heading up to Temple Pass. These hikers had just walked hundreds of miles over the hot flat desert of the Great Divide Basin, and were now entering The Winds. They were eager to experience the magical landscapes ahead, of which they’d heard so much about. We had a few brief conversations filled with anticipation and excitement. I remembered a bit of what it was like to be in their position, and hoped to bring some of that back home with me. We were back on the official CDT, with just a short hike back to our starting point.

But, we had one more night on the trail. As we set up camp above the churning whitewater of Little Sandy Creek, an American Dipper paid a visit. These aquatic songbirds make a living in rushing waters, snagging bugs from under the surface.

The next morning, it was an easy half-day hike back to our vehicle. But we’d now become temporary members CDT society – class of 2024 – this included picking-up a fellow hiker “Little Spoon” (or just Spoon for short), who’d had a minor setback by somehow misplacing his rolled-up tent somewhere behind. We ultimately got him back to Lander, where he later wrangled some logistics and got back on the trail northward. Determined hikers don’t stay stranded for long; somehow it all works out.

And that was it for the hiking. All I needed to do was catch a plane and be back to normal life. But in a tiny airport in the middle of Wyoming, there isn’t much buffer for error. A couple snafus with the airlines left me stranded there for about a day and a half. At least I had more birds to go find, like a flock of Common Nighthawks streaming through the quiet streets of Riverton.

Back at the airport among the sagebrush, I found a couple birds I’d never before seen – this Lark Bunting was the first, which curiously is neither a Lark nor a Bunting. But the birds don’t know the names we give them.

Finally, I spotted a Sage Thrasher as well. These birds also live in Eastern Oregon, but I’ve never managed to connect with one there. Sometimes, you have to go thousands of miles to find what should be right in front of you.

And then they fixed the plane. Off I went to the next adventure.